Rima Chahrouk

Hidden in the Savanna of Nigeria, abounded with rain forests, oil palm, and fertility; a flame lit an invigorating female empowerment, leadership, and competence.

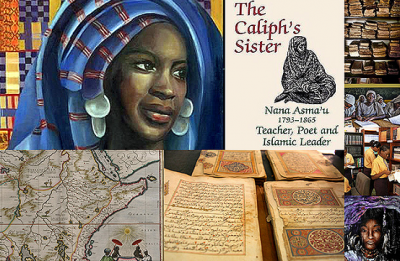

The light of her works continues to inspire and is practiced 153 years ensuing her death. Daughter of the Sokoto caliph, named after Asma’ bint Abu Bakr, she is Nana Asma’u.

The English recognize her as an early feminist icon. West African Muslims honor her, praise her efforts in augmenting the divine rights of women to learn and be active members in society, reinforcing dual gender roles, rights that had been selfishly absconded in preceding generations.

During her time, she influenced masses in West Africa, intellects from the Banks of the Nile, and scholars towards the peripheries of the Middle East.

A poet, scholar, teacher, polymath, and intellectual in her own right, Asma’u’s contributions to society annihilate apocryphal stereotypes of Muslim women in history, as devalued beings coerced to silence and domestic duty. Decades later, during the British colonization, British delegates would respond in shock towards the noble standard of intellectual milieu in which the Sokoto society operated.

When Jean Boyd was sent by the British to educate Nigerians, she records, “there is literacy here, there is God, so let me go back and try to learn from the very people I was supposed to educate”.

Beginning of the Story

The story of Asma’u begins before her birth, enveloped underneath the cognition, perception and wisdom instilled into her father.

Usman Fodio, was highly respected, an expert in Maliki Fiqh and follower of the Qadiriya order of Sufism. He was taught by his mother Hawa, and his grandmother Ruqaya.

The influence of his female teachers allowed him to realize the lack of female education retrograded skilled, enlightened, and prolific societies. As he grew, he encountered the rise of paganism and disorder in his homeland, resulting in the exile of him and his followers.

Followed with years of jihad and war, he found the Sokoto Empire in the land of Hausa. Usman sought to reinforce Islam saw that the greatest and most corrupt bid’ah (innovation) in a society was the marginalization of women in Education and community.

Usman Fodio wrote:

“Muslim women! Do not listen to the speech of those who are misguided and who sow the seed of error in the heart of another; they deceive you when they stress obedience to your husbands without telling you of obedience to God and His Messenger (May God show him bounty and grant him salvation), and when they say that the woman finds her happiness in obedience to her husband.

They seek only their own satisfaction, and that is why they impose upon you tasks which the Law of God and His Prophet never especially assigned to you. Such are the preparation of foodstuffs, the washing of clothes, and other duties which they like to impose upon you, while they neglect to teach you what God and the Prophet have prescribed for you.”

A Quran Translator, a Poet, and a Feminist

Asma’u was recognized for her intellectual merit, as she had already memorized the Quran, and learnt fiqh (jurisprudence) from a young age. Fluent in four languages Fulfulde, Hausa, Tamacheq and Classical Arabic, and a trinlingual author, she wrote Tafseer of the Quran, Biography of the Prophet, and Tibb al-Nabawi (Medicine of the Prophet).

During her pregnancy she translated the Quran into Fulfude and Hausa, as well as Ibn al-Jawzi’s Sifaatu Safwa, she has over 60 published works that have survived and are being studied until this day.

Asma’u orchestrated an educational movement, Yan Taru. A network of itinerant female educators, who were granted the title Jaji. The Jaji walked long distances to rural villages with the intention of educating women. The Jaji were responsible in transmitting the works and poetry of Asma’u.

The poetry of Asma’u was generally covered religious duties, resurrection, sins, repentance, paradise, and the love for the Prophet Muhammad. One such poem could entail 1,200 verses and take 6 hours to recite. Through her poetry Asma’u was able to reinforce the Islamic principles of the Quran and Sunnah.

Albeit Jajis were subject to cruel weathers and predators, they were instilled with Asma’u’s dedication to spread knowledge. In fact most women in Sokoto were poets, and well versed in classical Arabic literature. The society was in awe and love towards the Quran, it is therefore not surprising to encounter frequent references in Hausa and Fulfulde poetry alluring to the Quran.

Yan Taru continues to take place in West Africa and North America.

It was neither effective nor appropriate to expect rural women immersed in marriage and domestic duty to abandon their roles and come to Sokoto for an education.

Asma’u and her father found no virtue in knowledge that was not taught. In her role, both as an intellectual and a mother, she was aware by educating a woman, she was able to educate and reconstruct households, and through Jaji, Asma’u was able to develop a war-torn community into an intellectual power.

Asma’u’s achievements cannot be framed in an article, because years of continuing work cannot be outlined in a few minutes of reading. But I hope I have properly introduced this wonderful woman to today’s generation.

Source: About Islam

Quran

Quran

Add new comment